Information Warfare in Ireland: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Political Manipulation

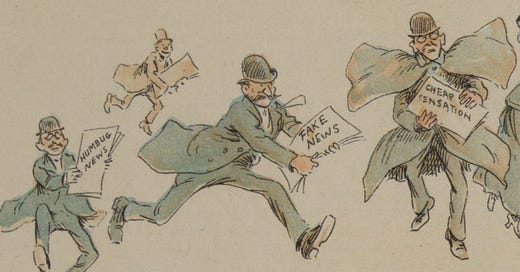

Ireland has a somewhat deeply rooted history of grappling with radicalism, a struggle often marked by societal divides tracing back to the days of British rule and beyond. Historically, the use of strategic information campaigns, including disinformation have long been utilized to exploit societal divisions and manipulate public perception. This is not confined to any one era or region, although worth noting that it is often associated with Russian tactics of information warfare1 due to well documented tactics used regularly during the Cold War, where Soviet and Western agencies engaged in efforts to undermine each other. For example, disinformation served as a strategic tool during the Cold War, with initiatives such as Radio Free Europe and Radio Marti. These efforts were designed to penetrate the Iron Curtain, broadcasting anti-communist sentiments to undermine Soviet influence in Eastern Europe and Cuba. The U.S., through the CIA’s Office of Policy Coordination, developed extensive propaganda networks, notably the “Mighty Wurlitzer,” which could transmit in multiple languages across communist territories2. This operation also involved the distribution of vast quantities of leaflets and other materials designed to sow dissent and encourage defection from communist regimes. The conflict in Northern Ireland, also known as The Troubles, saw various actors using media and propaganda to influence public opinion and international perceptions3. As the years have passed, so has our understanding of disinformation and originally seen primarily as a tool of statecraft during conflicts or political struggles, it has increasingly been recognized as a common tactic in domestic politics and insurgency strategies as well. Disinformation is not a novel invention but a sophisticated evolution of age-old propaganda tactics, often intertwined with military conflict and political machinations.4

A good introduction to the history of disinformation is by Heidi Tworek, found here.

Disinformation, Irish Republican Army and The Troubles

The Irish Republican Army (hereafter IRA), particularly during the Troubles from the late 1960s through the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, was involved in a protracted conflict against British rule in Northern Ireland. Their goal was to end British rule and reunite Ireland. The conflict was marked by violent acts, political maneuvers, and a significant propaganda battle. The IRA and its political wing, Sinn Féin, used propaganda to recruit members and garner support both domestically and internationally5. This propaganda often portrayed the IRA as freedom fighters defending Irish rights against British oppression6. Media portrayal and narratives, especially in regions with significant Irish diaspora such as the United States, sometimes depicted the IRA in a more positive light7. This can be viewed as part of an international influence campaign aimed at garnering support and funding. The British government and media also engaged in campaigns to depict the IRA as terrorists rather than freedom fighters8. The British efforts included controlling narratives to emphasize the violence and illegitimacy of the IRA’s actions. Such counter-narratives were intended to delegitimize the IRA's cause and reduce its support base both domestically and internationally. Studies and polls from the time often showed mixed public opinion on the IRA in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. While some community segments supported the IRA’s goals, their methods were frequently a point of contention.

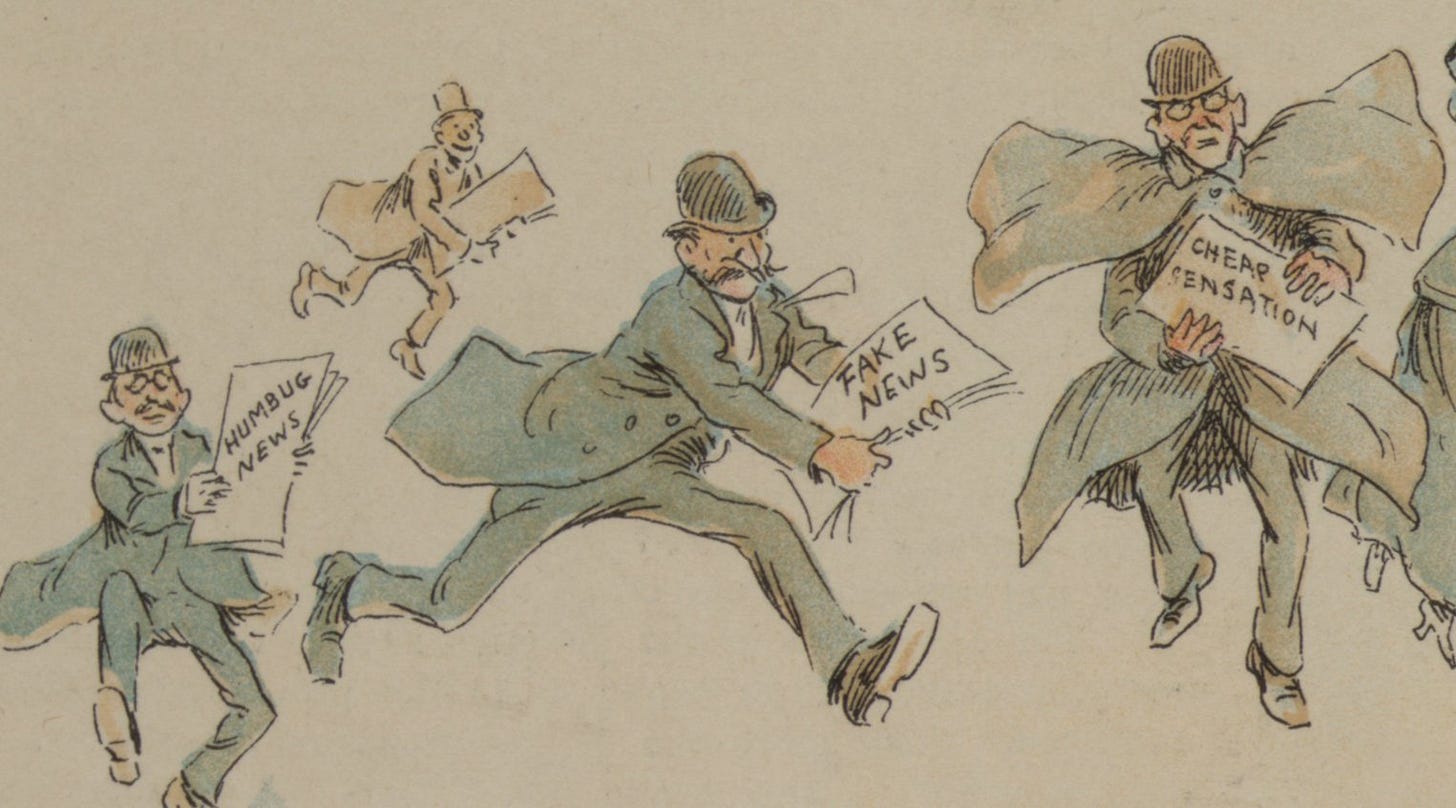

The influence of propaganda and disinformation on public opinion is hard to quantify precisely but is acknowledged as having played a role in shaping perceptions during the conflict. Academic investigations into the IRA often discuss the use of media and propaganda9. These studies examine how both sides of the conflict used information strategically to shape international and domestic opinion10. Scholars like Liz Curtis11 and Brian Feeney12 have discussed how narratives around the conflict were shaped by those involved to influence perceptions and policy. In Northern Ireland, disinformation campaigns effectively leveraged misinformation and covert propaganda to sow division and confusion among the population, exacerbating the already volatile situation during the Troubles. The British military and the Information Research Department (hereafter IRD) used various forms of unattributable propaganda to manipulate public perception and destabilize opposing groups. By spreading rumors and false reports such as the ‘IRA engaging in witchcraft’, or the misinformation about ‘explosive materials being temperature-sensitive’, British authorities aimed to discredit and delegitimize the IRA among the local communities and even within different factions of the IRA itself. This strategy not only fostered distrust within groups but also created a pervasive atmosphere of uncertainty and fear among the general populace, making it difficult for individuals to discern truth from fabricated narratives.13

This orchestration of confusion was not merely about undermining the IRA’s credibility but also aimed at controlling the narrative within the community to maintain a semblance of British authority and influence over Northern Ireland. By injecting misleading stories and creating fictitious threats, the British forces hoped to rally neutral and even sympathetic segments of the population against the IRA, painting them as a grave and immediate danger to peace and security. These tactics of information warfare contributed to a deeply polarized society, where misinformation led to real-world consequences, such as increased sectarian violence and communal rifts. The long-term impact was a fractured society, where truth became a casualty of conflict, leaving a legacy of mistrust that complicated efforts towards reconciliation and peace. We still see historical remanent of IRA-narratives being used in recent disinformation allegations from Russia, which Estonia has denied, claim that Estonia was involved in supplying arms to the IRA according to a document published on May 6th, 1996, it claimed the IRA was securing former Soviet arms including high-powered sniper rifles, heavy machine guns and explosives from Estonia. Russia claimed the IRA was securing the weapons via the extremist Estonian group Kajtselite, which it directly linked to Estonian intelligence14. This claim is a stark example of how disinformation campaigns are strategically used to foment tensions between countries and complicate international diplomacy, especially amid the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian conflict. By casting aspersions on Estonia and indirectly implicating Ireland, these unfounded accusations have the potential to strain diplomatic relations not only between the involved parties like the United Kingdom, but also with Russia. Such disinformation acts disrupt international trust, provoke defensive reactions from the targeted nations, and thrust them into unwelcome diplomatic quarrels or compel them to issue denials, as was the case with Ireland. This situation is only part of the broader tactic of employing disinformation as a weapon.

The Catholic Church and Disinformation in Irish Referendums

The debates surrounding Ireland's secularization and the separation from the Catholic Church's influence demonstrate a complex interplay of social dynamics and disinformation. Historically, there have been claims that reducing the Church's influence would erode Irish cultural identity. These assertions played on fears that secularization would undermine traditional values and social structures, which are often central to nationalist narratives. However, the evolution of Irish society in the subsequent decades shows a different outcome. Ireland has increasingly aligned with other modern, democratic European nations, embracing diversity and pluralism without losing its cultural identity. Scholarly analysis and census data indicate a significant shift in Ireland's religious landscape, with a noticeable decline in regular church attendance and a rise in individuals identifying as non-religious. This transition has coincided with legal and social reforms, such as the legalization of abortion and same-sex marriage, which mark Ireland's progression toward a more secular public policy framework. These changes reflect a broader global trend of secularization, where societies shift from organized religion to more secular governance and public life, often enhancing their democratic capacities and human rights protections in the process. While anti-secular narratives have sought to sow fear about the loss of cultural identity, the actual outcomes in Ireland have shown a strengthening of democratic institutions and an embrace of liberal values, suggesting that these fears were unfounded or exaggerated as part of a wider disinformation strategy used by right-wing groups.

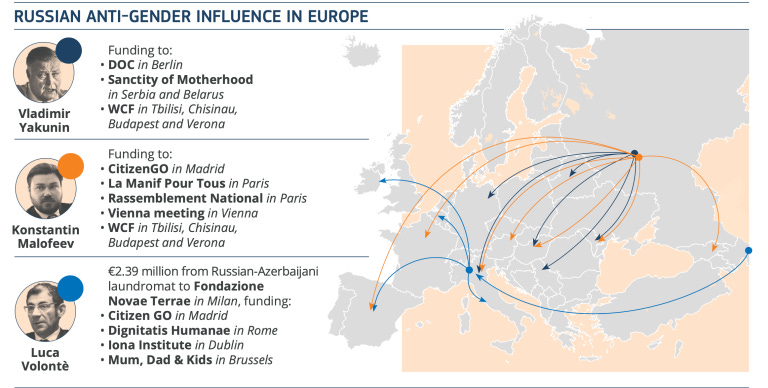

During Ireland's 2015 referendum on same-sex marriage, there were significant campaigns from both supporters and opponents. Some opponents, including certain conservative Catholic groups, propagated the idea that legalizing same-sex marriage would fundamentally harm societal values and the traditional family structure. These claims often exaggerated or misrepresented the potential impacts of the legislation, playing on fears rather than presenting factual arguments. For instance, some campaign materials suggested that children would be at risk if same-sex marriage was legalized, implying that children fare better in traditional male-female parented homes despite evidence to the contrary. The Iona Institute15, a conservative Catholic think tank, was particularly active, producing materials that stressed the importance of opposite-sex parents as ideally suited for raising children, which misrepresented broader sociological research on family structures16. Similar to the same-sex marriage campaign, the 2018 referendum to repeal the Eighth Amendment (which effectively banned abortion in almost all circumstances) saw a proliferation of misleading information. Some of this disinformation came from conservative and religious groups, both within and outside Ireland, who claimed that repealing the amendment would lead to extreme and widespread use of abortion, posing it as a threat to Irish moral and cultural fabric. One notable example was the circulation of claims that late-term abortions would become common if the Eighth Amendment was repealed. This was despite proposed legislation focusing on strict regulations around late-term abortions, similar to those in other European countries. Groups like Save the 8th17 and LoveBoth18, often supported by international anti-abortion organizations, were involved in disseminating these misleading narratives, using graphic images and emotional appeals as part of their strategy. There is also a wider claim that Iona Institute is linked to the wider anti-gender rights movements outside of Ireland, suggesting a foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) narrative as shown in the EPF19 report.

The debate over the Catholic Church's control of many Irish schools has included disinformation about the potential effects of secularizing the school system. Proponents of maintaining Church control have argued that removing or reducing this control would lead to a loss of moral education and a decline in educational standards. However, critics argue that this narrative overlooks the benefits of a more inclusive, secular education system that respects diverse beliefs equally. Misinformation often revolves around the idea that secular education would lead to moral relativism or a lack of values education, there is still some conversation and claim that it still controls the vast majority of Irish public schools and keeps finding new ways to maintain that control.20 The church’s historical role in some of Ireland's darker periods, such as the Magdalene Laundries and clerical child abuse, has also been subject to disinformation. When these issues received broader public attention, some church-related sources attempted to minimize the stories or discredit accusers. For example, some initial reactions to allegations of abuse in Church-run institutions included denials or deflection, suggesting that such accusations were exaggerated by the media or anti-Catholic sentiments. In the 1980s, the activities of paedophiles at the Kincora Boys Home, a Protestant institution in Belfast, were revealed and their ringleader, William McGrath. McGrath was not only a worker at Kincora but also, as it transpired in subsequent investigations, an influential political activist and agent of the British Intelligence service MI5. Some civil servants, Protestant ministers, politicians and security personnel were involved in a cover-up of what happened at Kincora21. This misinformation and disinformation aimed to protect the Church’s image by undermining the credibility of the survivors and the validity of their claims.

Four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than a thousand bayonets. - Napoleon

Transitioning to Modern Disinformation Weaponry

This historical context provides a poignant comparison to contemporary tactics used by groups, which leverage digital platforms to spread disinformation. Much like the British psyops during the Troubles, these modern entities utilize social media to sow discord, manipulate public opinion, and bolster their political agendas. The strategies involve creating echo chambers, disseminating polarizing content, and exploiting social fractures, similar to the "exploit any tendencies to disagreement and rivalry" approach seen in Northern Ireland. This comparative analysis underscores a persistent reliance on disinformation as a tool for those seeking to influence and control political landscapes, regardless of the era or technology available. Specifically focusing on Ireland, the legacy of such disinformation campaigns has led to an ongoing information warfare among different belief groups in both Ireland and Northern Ireland. The entrenched narratives and mistrust generated by years of propaganda have continued to influence interactions between communities. For instance, efforts to mitigate the impacts of disinformation are still critical in the post-Troubles era, as both societies grapple with the long-term consequences of manipulated truths which once fueled violent conflicts and deep-seated divisions and even more recent information on various declassified intelligence operations show that fabrications on both sides as a tactic.

Disinformation is not a novel invention but a sophisticated evolution of age-old propaganda tactics, often intertwined with military conflict and political machinations. The case of Radio Marti and similar operations illustrate the early recognition of media as a powerful tool for ideological warfare. Broadcasting in multiple languages, these radio stations aimed not just to inform but to influence, rallying support against Kremlin-backed regimes by promoting narratives that aligned with U.S. interests. Such efforts were not without consequences, occasionally resulting in "blowback," where disinformation campaigns would inadvertently affect domestic perceptions or international relations due to the propagation of unverified or false information. For instance, Radio Free Europe once broadcasted a report about a document allegedly from NKVD (Soviet intelligence) detailing brutal tactics against civilians, which, despite the truths in the accusations, turned out to be a forgery by Nazi intelligence22. In contemporary settings, disinformation has transcended traditional media platforms, magnified by the advent of digital technology and social media. The internet has democratized information dissemination, allowing state and non-state actors to broadcast their narratives globally at an unprecedented scale and speed. The case of Nova Resistência in Brazil exemplifies the modern evolution of disinformation networks. As an arm of the Syncretic Disinformation Network (SDN), Nova Resistência and associated entities like the Center for Syncretic Studies and Fort Russ News have been instrumental in propagating pro-Kremlin rhetoric23, aligning with Russian geopolitical interests by promoting disinformation on topics ranging from military conflicts in Ukraine and Syria to global issues like COVID-19 and climate change. This network, inspired by Russian philosopher Aleksandr Dugin’s anti-Western sentiments and his Fourth Political Theory, aims to dismantle the post-World War II international order by aligning far-right and hard-left movements. The operational strategy of these groups extends beyond mere propaganda; they actively engage in creating paramilitary and revolutionary movements, attempting to destabilize democracies and foster authoritarian regimes across different regions, including Latin America. Their activities highlight a sophisticated understanding of the power of narrative control, leveraging cultural and academic veneers to lend credibility to their disinformation campaigns.

The transition from traditional forms of propaganda to modern disinformation campaigns reveals several critical changes in tactic and scope. First, the speed and anonymity offered by digital platforms allow for more agile and covert operations. Unlike the radio broadcasts of the Cold War, digital disinformation can be continuously adjusted and targeted to exploit real-time global events and societal divides. Second, the scale of impact has expanded; digital disinformation campaigns can reach a global audience instantaneously, potentially influencing millions with minimal physical or financial investment. The use of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence in crafting and spreading disinformation represents a significant escalation in the arms race of information warfare. AI can generate realistic fake news and deepfakes, complicating the public’s ability to discern truth from manipulation24. This capability gives us an idea of the evolving nature of disinformation as a tool of warfare, extending beyond traditional political and military domains into the realm of information integrity and public trust.

Ireland and The Ongoing Disinformation War

In Ireland, the complex weave of disinformation has recently been illustrated in the narrative surrounding migration and asylum seekers. This scenario represents a modern adaptation of disinformation techniques, reflecting those utilized during the Cold War but evolved to exploit today's digital landscape. The disinformation surrounding migrants and asylum seekers in Ireland does not just float freely in the ether but is tactically placed and nurtured within social media platforms like Twitter/X and Telegram, where it can be tailored and amplified to reach susceptible demographics. These modern disinformation campaigns often bear the hallmarks of far-right25 conspiracy theories, such as the "#GreatReplacement" narrative26, which posits, in this case, that Irish people are being systematically replaced by immigrants. This baseless theory finds fertile ground among younger audiences, particularly when propagated by influential far-right figures. This reflects a strategic selection of target demographics, mirroring Cold War tactics where specific populations were targeted with tailored content. However, unlike the state-controlled media of the past, today's disinformation is often crowd-sourced to influencers who maintain an echo chamber that magnifies their messages. We can learn that although there is a shift in the medium and mode of delivery, there is a continuity in intent and effect. Where once the CIA attempted and successfully orchestrated public opinion through covertly funded newspapers or radio shows, today's operatives, sometimes state-backed as evidence has shown27, and sometimes not, manipulate public opinion through decentralized, yet highly coordinated online campaigns in the form of tweets, chat groups, online videos and podcasts28. These modern methods harness the algorithmic power of social media, designed to engage users by reinforcing existing beliefs and biases, thereby facilitating the spread of disinformation more efficiently than any physical leaflet or broadcast could have during the Cold War or another more recent example, the Iraq invasion29 where the US Air Force had conducted leaflet drops targeting both civilians and military personnel.

The specific case of migration and LGBTQ+30 play a crucial role in the recruitment and radicalization of youth. Recent studies highlight the growing influence of far-right extremism in Ireland, facilitated largely through online platforms like X, which have become hotbeds for the spread of misleading and harmful content.31 The tactics employed by far-right groups often include portraying migrants and asylum seekers as existential threats and spreading harmful falsehoods about the LGBTQ+ community. These narratives are specifically designed to resonate with younger audiences, employing emotionally charged rhetoric and conspiracy theories that can appeal to those feeling disenfranchised or anxious about cultural and demographic changes and by framing migration in existential terms, these groups not only justify their xenophobic ideologies but also paint themselves as the last line of defense in preserving the 'purity' of the nation. This manipulation of public sentiment is not random but a calculated component of their recruitment strategy, designed to inflame tensions and expand their base, not dissimilar to tactics used to recruit insurgency or paramilitary activism. These online campaigns are successful at creating echo chambers that amplify these messages, making them appear more mainstream than they are. The use of social media algorithms further helps in targeting susceptible demographics, creating a feedback loop that not only spreads disinformation but also mobilizes individuals for offline activities, such as protests and acts of vigilante-style violence. The recruitment and influence into far-right groups is thus facilitated by these disinformation campaigns, which play on fears and prejudices, while offering a community of like-minded individuals. This mechanism mirrors historical disinformation tactics, such as those used during the Cold War to create dissent, but adapted for the digital age where the spread is faster and can be more specifically targeted.

This phenomenon was particularly evident during election cycles and public referendums, where far-right groups launched coordinated disinformation campaigns to sway public opinion and disrupt the democratic process. These campaigns often involve the creation of fake news sites, the manipulation of factual content, and the strategic use of bots and trolls to spread their distorted messages widely. There is ample research and evidence on election meddling using these tactics. This weaponization of disinformation has real-world consequences, leading to increased polarization and, at times, inciting violence. For instance, in Ireland and other various European countries, far-right groups have been linked to arson attacks on refugee centers, assaults on minorities, and large-scale protests against government policies perceived as pro-immigration. These acts of violence are often precipitated by sustained online campaigns that dehumanize immigrants and refugees, depicting them as the root cause of societal ills. The Institute of Strategic Dialogue (ISD)32 did an analysis on disinformation and misinformation in Ireland, and looked at over 13 million posts from 2020 to 2023 across various online platforms, revealing significant participation by far-right actors who used these platforms to proliferate their ideologies. The presence of disinformation is increasingly observed in discussions that quickly move from online platforms to physical gatherings, such as anti-lockdown protests or anti-immigration rallies, showing a clear link between online disinformation and offline radicalization and violence. This also suggests that disinformation serves as a tool for radicalization by promoting extremist views among youth and other susceptible groups. Historically, Ireland's struggles with radicalism were influenced by various actors using media and propaganda, especially during The Troubles. Today, these methods have adapted to the digital age, where misinformation is crafted to be more engaging and is spread quickly and efficiently through social media. The disinformation environment in Ireland has become increasingly complicated due to advancements in technology that facilitate the swift spread of false narratives tailored to specific audiences. This has led to the radicalization of younger segments of the population who, as history demonstrates, are likely to engage in physical actions when incited.33

Mark Galeotti, "Active Measures: Russia’s Covert Geopolitical Operations," Marshall Center Security Insight, no. 31 (2019).

Rodney Carlisle, Encyclopedia of Intelligence and Counterintelligence: Journalism and Propaganda (Routledge, 2005), 355-365.

Rory Cormac, Disrupt and Deny: Spies, Special Forces, and the Secret Pursuit of British Foreign Policy (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Iztok Podbregar and Teodora Ivanuša, The Anatomy of Counterintelligence: European Perspective (Bentham Books, 2016).

John Coakley and Michael Gallagher, Politics in the Republic of Ireland (1992).

Richard English, Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA (2003), 145-165.

Patrick Bishop and Eamonn Mallie, The Provisional IRA (1987), chapter: "Armed Propaganda".

David McKittrick, Making Sense of the Troubles: A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict, 130-180.

Celeste Michelle Condit (Editor) and Simon Cottle, "Reporting the Troubles in Northern Ireland: Paradigms and Media Propaganda," in Reporting the Troubles, 282-296.

Deric Henderson, Reporting the Troubles 2 (2022).

Liz Curtis, The Cause of Ireland, from the United Irishmen to Partition (Beyond the Pale Publications).

Brian Feeney, Short History of the Troubles.

"The war against the IRA and the birth of fake news," British Telegraph, 2018.

Brian Hutton, "State Papers: Ireland Feared Being Drawn into Estonia-Russia IRA Arms ‘Disinformation’ Row," 2022.

Iona Institute, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iona_Institute.

Louisa McGrath, "Countering The Iona Institute," L2015.

Save The 8th Amendment, https://www.save8.ie/.

LoveBoth, https://loveboth.ie/.

European Parliamentary Forum for Sexual & Reproductive Rights (EPF), https://www.epfweb.org/.

Barry Purcell, "A Constant Struggle: Catholics Still Control Irish Schools," 2022.

C. Moore, Kincora Scandal: Political Cover-up and Intrigue in Ulster (Marino Books, 1996).

Carlisle, Rodney, Encyclopedia of Intelligence and Counterintelligence: Journalism and Propaganda (Routledge, 2005), 355-356.

Exporting Pro-Kremlin Disinformation: The Case of Nova Resistência in Brazil, Global Engagement Center Special Report, 2023.

Facing Reality? Law Enforcement and the Challenge of Deepfakes: An Observatory Report from the Europol Innovation Lab, 2022.

"Far-Right Hate and Extremist Groups," https://globalextremism.org/ireland/.

The “Great Replacement”, https://www.isdglobal.org/explainers/the-great-replacement-explainer/

David Wright, Richa Kumar, and Evangelos Markatos, https://project-athena.eu/eternal-vigilance-is-the-price-of-liberty/

Squire, Megan, and Gais, Hannah. "Inside the far-right podcast ecosystem, part 1: building a network of hate." Southern Poverty Law Center, Hatewatch. (2021). https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2021/09/29/inside-far-right-podcast-ecosystem-part-1-building-network-hate

Propaganda pamphlets of the United States of the Iraq War - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Propaganda_pamphlets_of_the_United_States_of_the_Iraq_War

Beatrice Fanucci, "'Far-right Influence Growing in Ireland, Major Study Finds," 2023.

Gallagher, Aoife, O'Connor, Ciarán, & Visser, Francesca. "An investigation into the online mis- and disinformation ecosystem in Ireland."

Gallagher, Aoife, O'Connor, Ciarán, & Visser, Francesca. "An investigation into the online mis- and disinformation ecosystem in Ireland."

Sara Zeiger and Joseph Gyte, "Prevention of Radicalization on Social Media and the Internet," in Handbook of Terrorism Prevention and Preparedness, Chapter 12.