Managing and Recruiting Informants: A Closer Look at the RUC’s Strategy

In the Northern Ireland conflict, the role of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and its Special Branch (SB) in managing informants has long sparked a mix of controversy, ethical debates, and reassessments. This Substack article is about the RUC's informant strategies during the tumultuous years of intelligence operations, where the line between ethical obligations and operational effectiveness was often blurred. The early period of the Troubles marked a significant intelligence vacuum for the RUC, catalyzing the development of a robust informant network. This network was not merely a tool of law enforcement but became central to the broader intelligence ecosystem that included MI5 and the British military. The integration and effectiveness of informants were underpinned by the RUC's dual objectives: disrupting terrorist activities and securing intelligence that could steer political negotiations.

Early Use of Informants: The 1970s

The 1970s marked a pivotal decade in the history of Northern Ireland, characterized by escalating violence and deepening political divides. The split within the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which led to the formation of the Provisional IRA (PIRA), compounded the volatility. This split not only intensified the conflict but also plunged the RUC SB into a profound intelligence vacuum. Confronted with this challenge, the RUC SB's decision to deploy informants within various paramilitary groups was not only a strategic imperative but also a necessary response to an increasingly unpredictable security environment. The civil rights movement, inspired by global events and driven by the Catholic nationalist population's demand for equal rights, was met with severe resistance from the Protestant unionist community and often by the state itself. The RUC, predominantly composed of unionists, was viewed with suspicion and outright hostility by the nationalist community, which perceived it as an instrument of state oppression rather than a neutral law enforcement agency. This perception significantly hindered the RUC's ability to gather intelligence from the nationalist areas, precisely where the PIRA was consolidating its strength. The situation was exacerbated by the PIRA's clandestine nature and its cellular organizational structure, which effectively shielded its activities from the prying eyes of law enforcement.'

The Strategic Imperative for Informants

In response to these challenges, the RUC SB began embedding informants within paramilitary groups. This strategy was not unique to Northern Ireland; informants have long been a fundamental element of intelligence operations worldwide, providing insights that are not obtainable through other means of surveillance or intelligence gathering. In the context of Northern Ireland, the use of informants was crucial for several reasons, informants provided the RUC with eyes and ears within tightly knit communities that were otherwise impenetrable. This access was vital not only for gathering intelligence on planned violent activities but also for understanding the community dynamics that fueled the conflict and the dynamic nature of the conflict necessitated timely and actionable intelligence. Informants could offer immediate insights into the planning stages of violent acts, potentially saving lives and preventing escalation, but also beyond gathering intelligence, informants could act as agents of disruption within their organizations. By feeding misinformation or creating distrust, they could effectively destabilize paramilitary operations without direct confrontation. The deployment of informants, however, was fraught with ethical and operational challenges. The ethical dilemma was clear: by recruiting informants within these groups, the RUC SB was often forced to overlook, and sometimes indirectly facilitate, criminal activities committed by these informants as a trade-off for valuable intelligence. This moral quandary was compounded by the potential for abuse of power, where lines could blur between using informants for genuine intelligence purposes and manipulating them to achieve broader political objectives. Operationally, the use of informants required delicate handling. The informants' safety was a constant concern, as their exposure could lead to lethal retribution from their own groups. Moreover, managing the information flow from informants to ensure it was credible and actionable without compromising their identity was a

The use of informants during this period can be defended as not only necessary but decisive in preventing the conflict from spiraling further out of control. The intelligence gathered through informants likely prevented numerous violent acts, saved lives, and provided the RUC with crucial insights into the inner workings of paramilitary groups, which were essential for any form of negotiation or peace-building efforts.

1980s: The Height of the Troubles

As violence escalated, the SB's reliance on informants grew. The 1980s in Northern Ireland, often referred to as the "Height of the Troubles," was a period marked by intensified conflict and a corresponding escalation in the use of informants by security forces. This decade witnessed some of the most controversial and morally complex operations in the history of the RUC SB and the British Army.

The Emergence of Brian Nelson and The Pat Finucane Killing

Among these, the case of Brian Nelson stands out as particularly emblematic of the challenges and ethical dilemmas inherent in intelligence operations during this turbulent time. Brian Nelson, a high-ranking member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), was recruited in the early 1980s by the British Army's Force Research Unit (FRU), a secretive entity tasked with gathering intelligence on paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland. Nelson's role within the UDA was significant due to his position as the chief intelligence officer, which gave him access to sensitive information and operational planning. As an informant, Nelson was uniquely positioned to provide the FRU with detailed inside knowledge of UDA operations. His intelligence was crucial in helping the British Army and the RUC understand the internal dynamics of the UDA and to some extent control its activities. Nelson's information led to the prevention of certain attacks and helped mitigate the UDA's operational effectiveness by leading to the arrest of key figures, that said, Nelson's activities extended beyond mere information gathering. He was actively involved in the targeting and planning of assassinations, a role that directly contributed to several killings throughout the 1980s. His involvement in these activities highlights the darkest aspects of informant use, where the line between gathering intelligence and participating in criminal activities becomes blurred.

The most notorious incident associated with Nelson was the assassination of Pat Finucane in 1989. Finucane, a solicitor known for representing IRA members, was shot 14 times in front of his family by UDA gunmen. This killing attracted international condemnation and has been the subject of extensive investigations suggesting collusion between Nelson (and thus indirectly the FRU) and the killers. Finucane's murder was a watershed in the conflict in Northern Ireland, drawing attention to the extent of collaboration between state forces and loyalist paramilitaries. Reports and inquiries later suggested that Nelson had provided the intelligence that led to Finucane's targeting, with at least some level of awareness and possibly direct facilitation from his FRU handlers. The use of Nelson as an informant raises profound ethical questions about the limits of acceptable practices in intelligence work. On one hand, Nelson's intelligence undoubtedly saved lives by preventing several planned attacks. On the other hand, his involvement in violent activities, including murder, poses serious moral challenges because by allowing Nelson to remain active in the UDA and participate in its violent campaigns, the FRU and by extension the British Army were complicit in those crimes. This complicity challenges the ethical foundations of any law enforcement or military operation.

The revelations about Nelson and the broader implications of state collusion with paramilitary groups severely damaged the credibility of the security forces among the nationalist community, exacerbating tensions and undermining the peace process.

1990s: Informants and the Peace Process

The 1990s were a crucial decade for Northern Ireland, marked by significant political shifts and attempts at peace negotiations. This period, however, also spotlighted the contentious role of informants used by security forces, particularly within the context of the PIRA. One of the most controversial figures was an informant known by the codename "Stakeknife", widely alleged to be Freddie Scappaticci, who was reportedly a high-ranking member of the PIRA’s internal security unit. This unit was notoriously responsible for counterintelligence activities within the IRA, including the identification and execution of informers within the organization.

The Role and Impact of Stakeknife

Stakeknife's involvement with the British security forces, especially the FRU, a covert military intelligence unit, highlights the complex and morally ambiguous landscape of informant use in Northern Ireland. As an insider within the PIRA, Stakeknife was in a position to provide valuable intelligence that was crucial for thwarting attacks and saving lives. However, his role also involved participating in and facilitating some of the IRA’s most brutal internal security measures, including the interrogation and execution of suspected spies. This dual role presents a fundamental ethical dilemma: the use of a valuable informant who is simultaneously involved in reprehensible activities. The British security forces' reliance on Stakeknife was indicative of a broader strategy that often prioritized immediate intelligence gains over long-term ethical considerations. The use of an informant like Stakeknife during the peace process era was fraught with significant risks. On one hand, such informants were indispensable for obtaining insights into the IRA’s operations, which could potentially lead to saving lives and preventing violence. On the other hand, the involvement of security forces in abetting or overlooking the criminal activities of their informants posed severe ethical questions and risked undermining the legitimacy of the peace process itself.

One of the most pressing issues was the protection offered to Stakeknife by his handlers, which allegedly allowed him to carry out his role within the IRA with impunity. Reports suggest that his handlers might have intervened or turned a blind eye to prevent his exposure, thus indirectly contributing to the activities of the IRA’s internal security unit. This included potentially obstructing police investigations and criminal proceedings that could have exposed his role and destabilized the informant network within the IRA. The revelation of Stakeknife’s role and the extent of his activities had a profound impact on public trust, particularly among nationalist communities in Northern Ireland. These communities were already skeptical of the peace process and the motives of the British government. The discovery that an informant was deeply involved in such activities complicated efforts to foster reconciliation and trust between the opposing sides.

Post-1998: The Good Friday Agreement and Beyond

The signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 marked a historic milestone in the peace process in Northern Ireland, but the use of informants by security forces remained a deeply contentious issue. This period was characterized by ongoing reliance on informants despite the new peace landscape, and it brought to light significant challenges associated with their management and oversight, especially in cases where informants were involved in serious criminal activities.

The Case of Raymond McCord Jr, The Inquiry and Its Implications

One of the most significant cases in the post-Agreement era was the murder of Raymond McCord Jr. in 1997, which became a pivotal moment for public and political scrutiny of informant handling in Northern Ireland. McCord Jr., a 22-year-old from Belfast, was allegedly killed by a unit of the UVF, led by Mark Haddock, who was later revealed to be a police informant. This case exposed the problematic aspects of informant management by the RUC, particularly the failure to control and oversee informants involved in serious crimes, including murder. The revelations about Haddock's role and his relationship with his handlers raised profound questions about the ethics and effectiveness of using criminal informants. It highlighted the dangers of the security forces' reliance on informants who were deeply embedded within violent paramilitary groups and who continued to participate in criminal activities, ostensibly under the protection or oversight of their handlers. The public outcry following the revelation of the circumstances surrounding McCord Jr.'s murder led to an inquiry that scrutinized the practices of informant handling within the RUC. This inquiry not only confirmed that Haddock was an informant but also detailed how his handlers had allegedly protected him from prosecution for a series of crimes, presumably to maintain his utility as a source of intelligence. This situation illustrated the problematic nature of a system that allowed informants to operate with a degree of impunity, ostensibly in the interest of a greater security goal. The inquiry into McCord Jr.'s death brought to light the stark ethical dilemma faced by law enforcement: balancing the necessity of gathering intelligence with the imperative of preventing crime and administering justice.

The period following the Good Friday Agreement necessitated a reevaluation of the role of informants in a peace-oriented society and while the peace process aimed to end the violence and promote reconciliation, the continued use of informants who engaged in criminal activities contradicted the principles of the Agreement and undermined public trust in the peace process and in law enforcement agencies.

Informants: The Necessary Evil (Adapted from David Lowe)

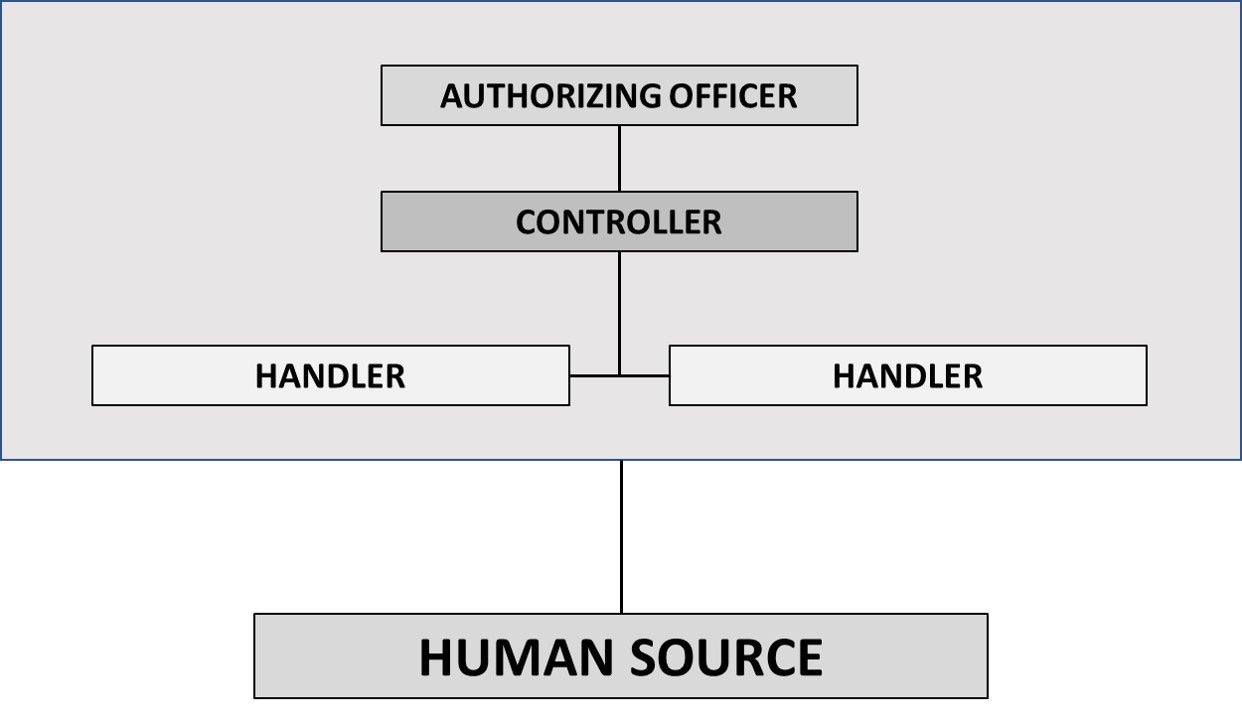

It is recognized by both practitioners and academics that the use of informants is central and an important source of information in criminal investigations The most effective informant is the person who has contact/involvement with criminals and Greer’s categorization of informants is still a useful model to use. Greer states the categories of informant hinge on two variables, one being the relationship between informants and the people upon whom they inform with and the second being the relationship with the police to whom the informant supplies their information.

He categorizes informants as follows:

“Casual observer” who is an “outsider” as they have no connection or relationship with the person, they pass information onto the police as they have observed an incident and bring it to the attention of the police.

“One-off accomplice witness” who is an “insider” as they have some connection or relationship with the person on whom they are passing information onto the police. They are passing information onto the police out of contrition or because of the possibility of lesser charges.

“Supergrass” who not only has a connection or relationship with the person on whom they are passing information onto the police, but they also have inside information on the crimes being planned or committed by that person, and the supergrass informs the police of multiple incidents of crime.

Recruiting Informants

The traditional way of recruiting informants is with persons who are in police detention following their arrest or with every offender police officers meet. This method of informant recruitment has changed little over the years. The SB recruited the “paid-in-kind” informant who had been arrested and recruited during their suspect interview by the officers as officers had some form of hold over the informant including the threat of bringing charges for some minor offenses. This method of informant recruitment has been criticized as being held in police custody is characterized by enforced dependency, frustration, isolation, and fear; hence, it is not surprising that those detained in police custody are more likely to succumb to propositions to provide information. This has been a global method of informant recruitment. In Australia’s New South Wales state’s Independent Commission Against Corruption’s 1993 discussion paper on police informants, while it mentions how police officers were encouraged to cultivate informants, it says there has been little guidance in applying the most appropriate ways of recruiting them. Citing New South Wales detective training material, it says that every person arrested is a potential informant and they should be cultivated accordingly adding.

The police practice of “turning” or “flipping” suspects into informants following arrest is an area that has courted academic and media controversy. Using public police policy documentation, found that a range of tactics were used by officers to recruit informants, “…according to the officer’s assessments of the individual concerned and what they believed would be the most effective approach”. Examining Canadian police documents, found that the methods recommended to encourage offenders to inform was not through physical coercion but through the use of mind games. All the empirical work on informants found that a variation of mind games were used by the police to recruit informants ranging from:

Exaggerating the offenses a suspect may be charged with.

Threatening the potential of long prison sentences the suspect may receive should they be charged and tried for the offenses they were arrested for.

Where there is more than one suspect, officers would imply to one that the other suspect is talking and about to make a deal .

The financial implications of informing that can range from the officers saying how much an informant can earn or, if the suspect does not inform, what they could lose if convicted.

Appendix

Jon Moran (2010) Evaluating Special Branch and the Use of Informant Intelligence in Northern Ireland, Intelligence and National Security, 25:1, 1-23, DOI: 10.1080/02684521003588070

U.S. Department of the Army and U.S. Marine Corps, Counterinsurgency, FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2007).

The Intelligence Community in Counterinsurgency: Historical Lessons and Best Practices, Andrew C. Albers et al (2009)

Intelligence, Surveillance and Informants: Integrated Approaches, Maguire et al (2006)